MIT Sustainability Summit

2024/05/26

Priscilla Clark

Oaksight attended the MIT Sustainability Summit on April 24, 2024. Check out our full recap!

Overview

The MIT Sustainability Summit explored pathways to a more sustainable future by examining interconnected challenges and solutions across three tracks (1) agriculture and biodiversity, (2) the built environment, and (3) transportation. The conference featured speakers like Sandrine Dixson-Declève, who advocated for a significant redrawing of the global economic “gameboard”, and Michael Raynor, who proposed Virtual Commodity Purchase Agreements (VCPAs) to address decarbonization challenges in hard-to-abate sectors.

Discussions emphasized the importance of technological innovation, policy interventions, and a systems-thinking approach to address complex issues like climate change and biodiversity loss. Drawing on the ‘unconference’ theme, the summit did an excellent job fostering collaboration among participants, with the three tracks each using the afternoon to derive potential solutions for case studies.

Morning Sessions

From “Limits to Growth” to “Earth for All”

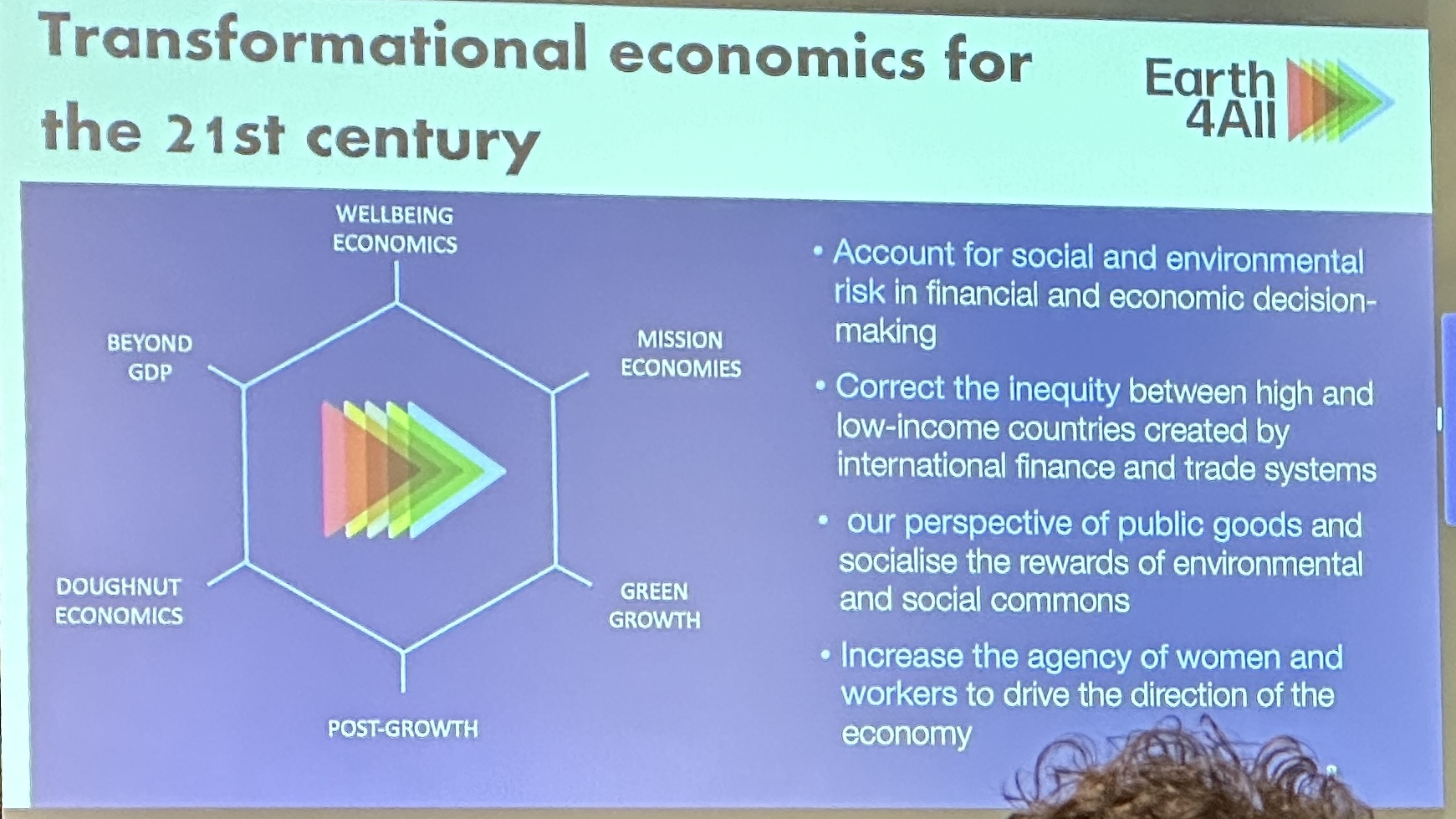

Sandrine Dixson-Declève, President of the Club of Rome, emphasized the need for a 21st-century economic transformation. This transformation involves three key elements: (1) factoring social and environmental risks into financial and economic decisions, (2) rectifying the economic imbalance between high and low-income countries caused by current international finance and trade systems, and (3) empowering women and workers to shape the future of the global economy.

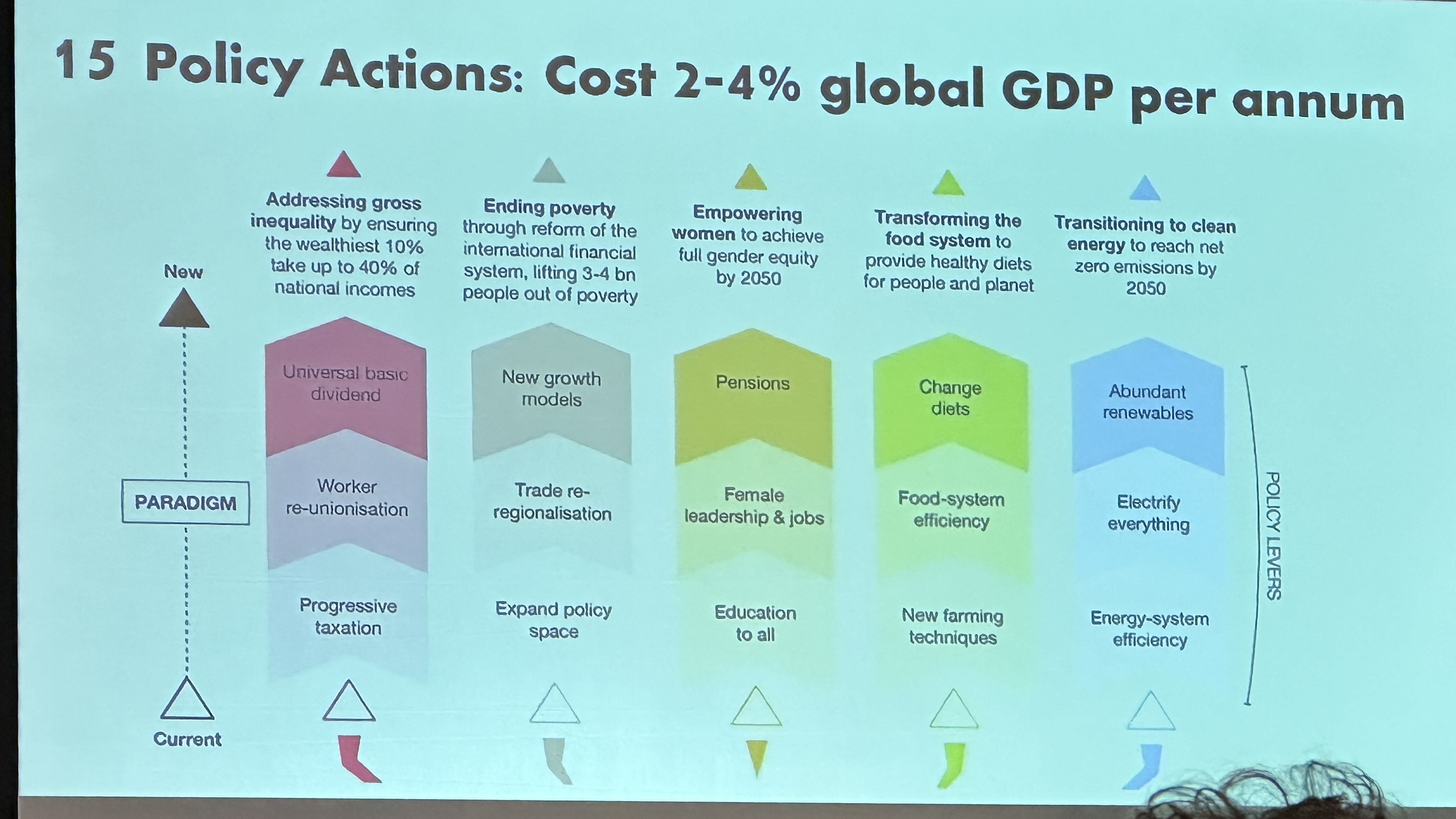

Dixson-Declève proposed 15 policy actions to drive this transformation, estimating their cost at 2-4% of global GDP annually. These actions target four key areas:

- Addressing Gross Inequality: Limiting the income of the wealthiest 10% to a maximum of 40% of national incomes through measures such as progressive taxation, worker re-unionization, and a universal basic dividend.

- Ending Poverty: Reforming the international financial system to lift 3-4 billion people out of poverty, expanding policy space, promoting trade re-regionalization, and fostering new growth models.

- Empowering Women: Achieving full gender equality by 2050 by ensuring education for all, promoting female leadership and employment opportunities, and guaranteeing pensions.

- Transforming the Food System: Providing healthy diets for all while protecting the planet by implementing new farming techniques, increasing food system efficiency, and promoting dietary shifts.

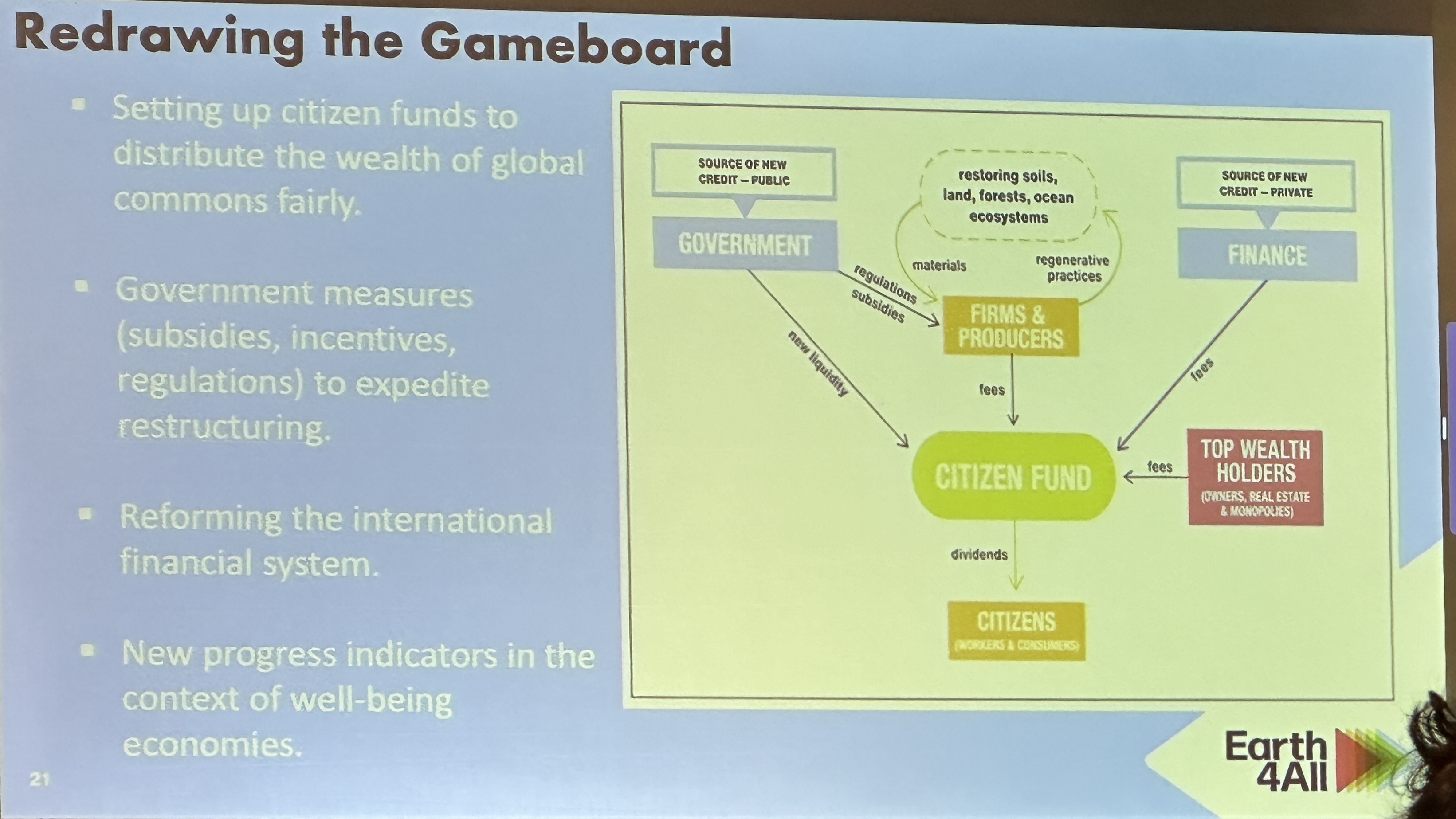

In addition to these policy actions, Dixson-Declève advocated for a significant redrawing of the global economic “gameboard”. This includes establishing citizen funds to ensure equitable distribution of global commons wealth, implementing government measures like subsidies, incentives, and regulations to accelerate economic restructuring, reforming the international financial system, and adopting new progress indicators aligned with well-being economies.

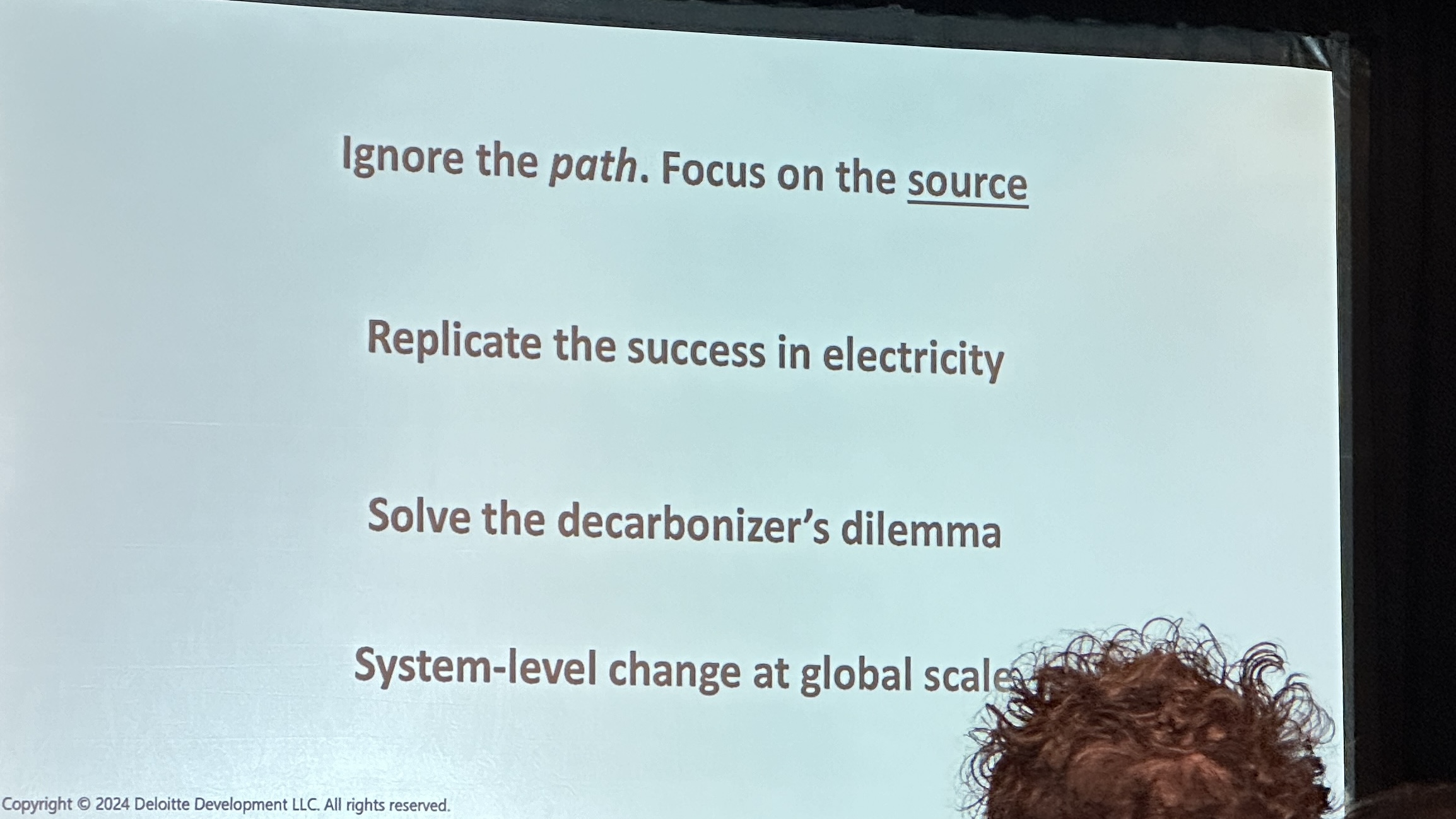

The Decarbonizer’s Dilemma

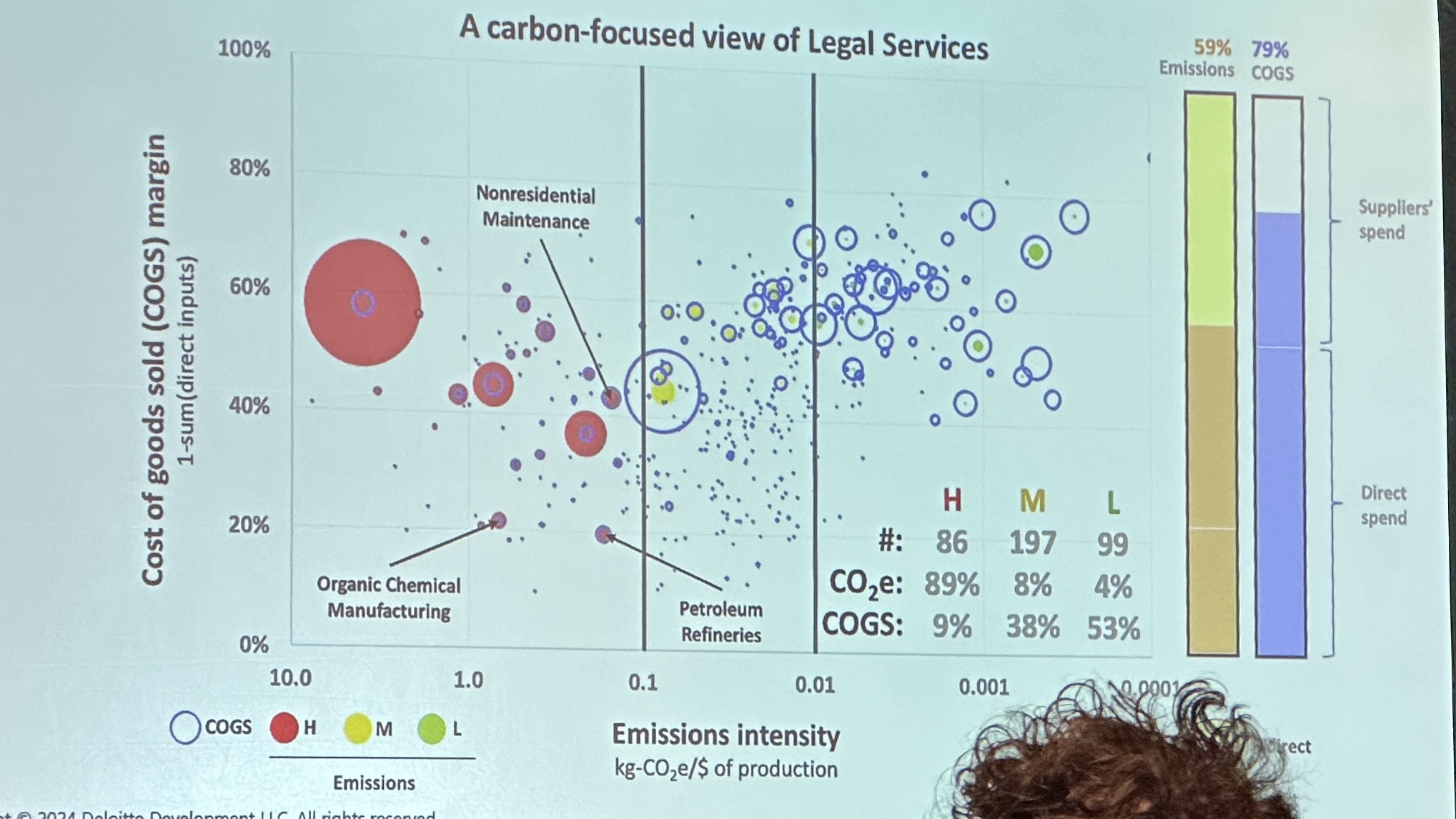

Michael Raynor, Managing Director at Deloitte, tackled the decarbonization challenge faced by hard-to-abate (HTA) sectors. Highlighting the limitations of incremental innovations, he argued that large-scale disruptive innovation is key to achieving significant emission reductions in these industries. HTA sectors, crucial for economic activity, face significant barriers to decarbonization. While technologies for lower-carbon production exist, they often come at a higher cost, making it challenging for companies to adopt them without eroding their profit margins.

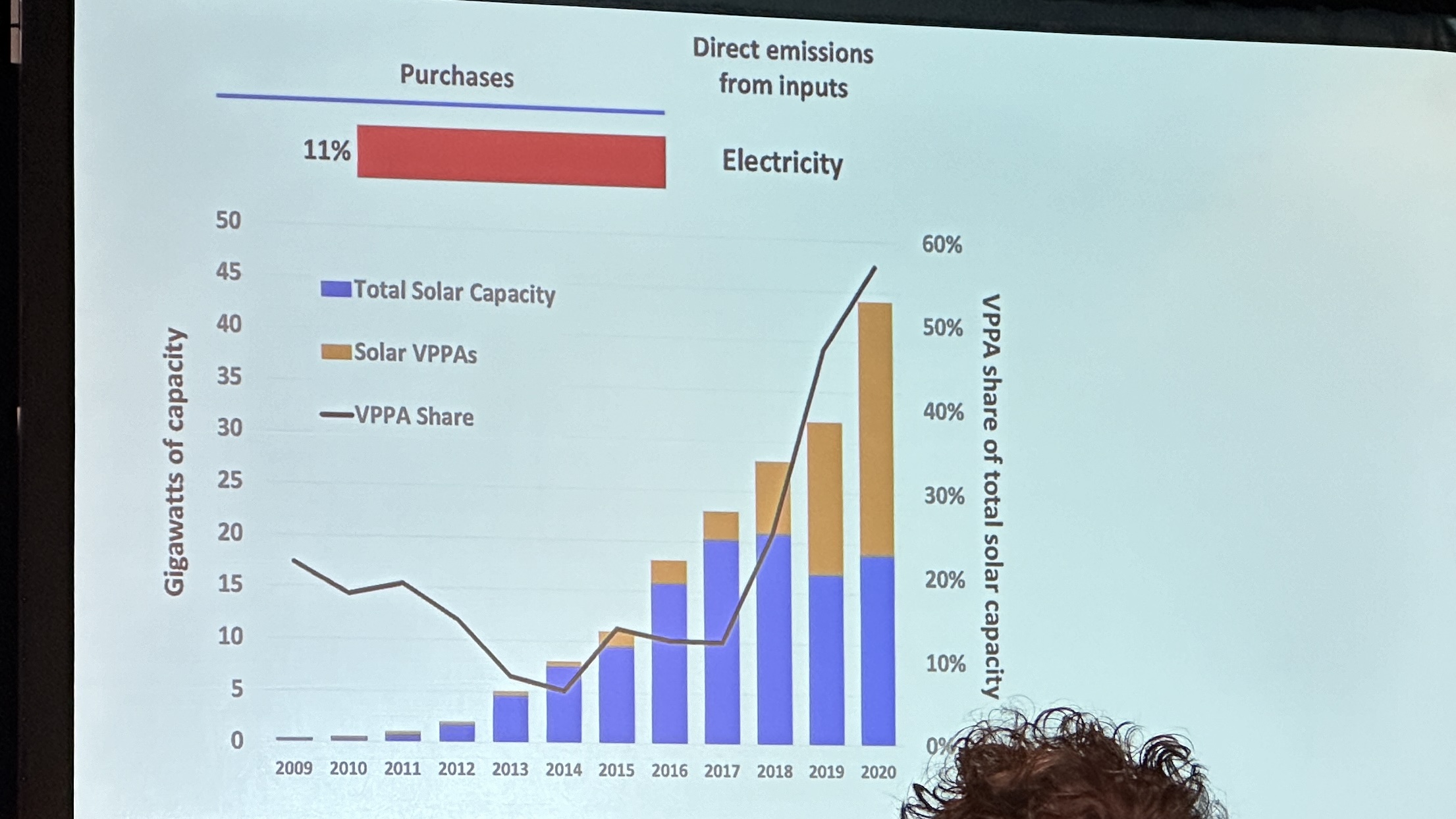

Raynor proposes a new market mechanism called Virtual Commodity Purchase Agreements (VCPAs) to address the decarbonization challenges faced by hard-to-abate (HTA) sectors. VCPAs are inspired by the success of Virtual Power Purchase Agreements (VPPAs) in accelerating the adoption of renewable energy.

VPPAs as a Model for Change

VPPAs have been instrumental in driving the growth of renewable energy. They function by allowing buyers to purchase the environmental attributes of electricity separately from the electricity itself. This mechanism enables companies to support renewable energy projects even if they don’t directly consume the electricity generated.

VCPAs would function similarly to VPPAs but apply to commodities such as steel, concrete, and other HTA inputs. Companies would commit to purchasing a certain quantity of a commodity at a guaranteed price, providing producers with the financial security to invest in lower-carbon production methods.

Advantages

- Address Supply Chain Complexity: VCPAs overcome the challenge of tracing the origin of commodities in intricate supply chains, allowing companies to contribute to decarbonization efforts without disrupting existing supplier relationships.

- Mobilize Demand for Decarbonized Commodities: By creating a market for low-carbon commodities, VCPAs provide a financial incentive for producers to adopt cleaner technologies, accelerating the transition to a net-zero economy.

- Targeted and Temporary Subsidies: VCPAs offer a mechanism for targeted and time-limited subsidies, supporting the initial adoption of low-carbon technologies until they achieve cost-competitiveness.

The Tesla Analogy

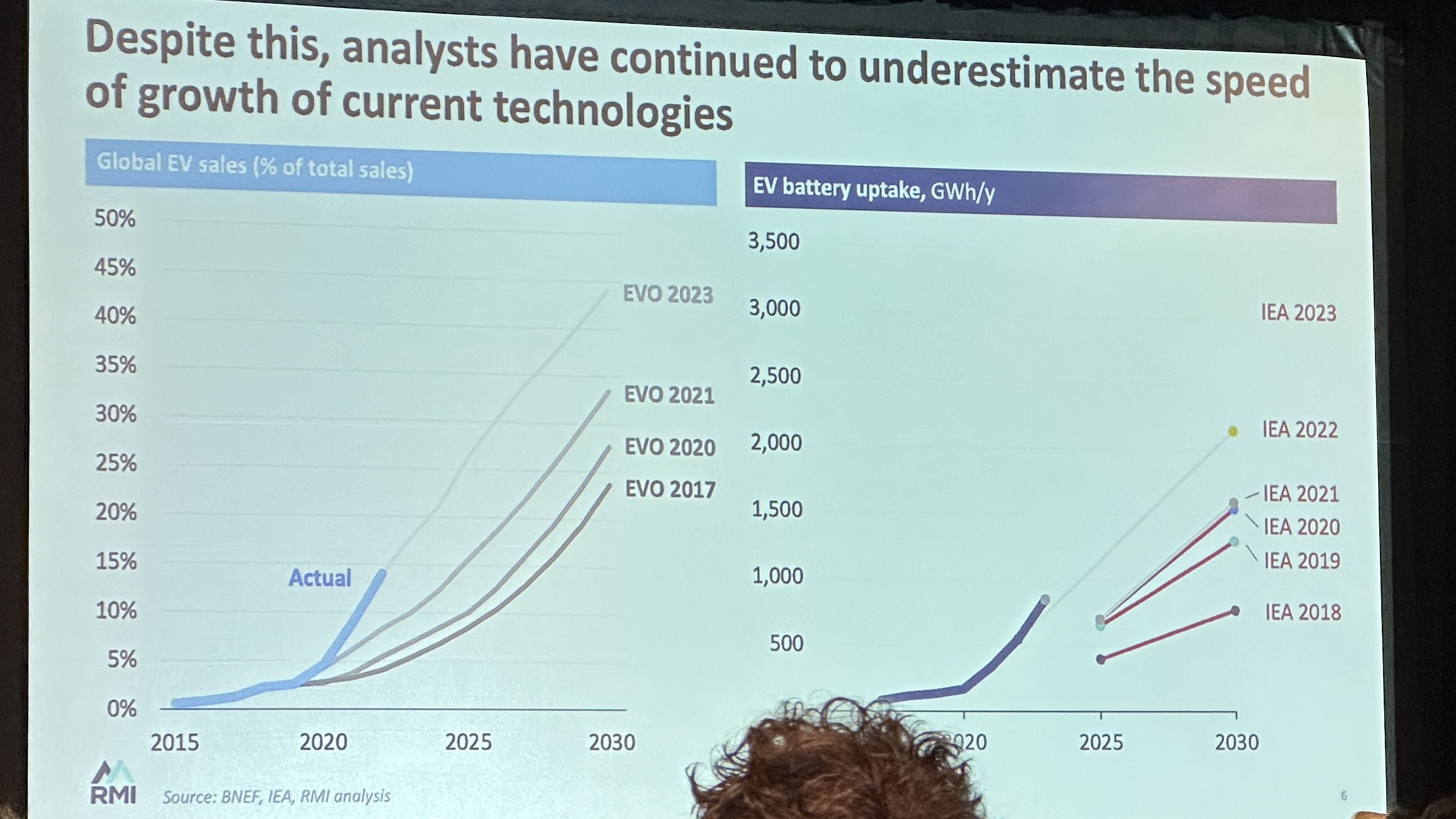

Raynor highlights Tesla’s impact on the automotive industry as an example of how a relatively small player can trigger large-scale transformation. Tesla’s early focus on electric vehicles, despite their higher initial cost, demonstrated the viability of the technology, prompting established automakers to accelerate their own EV programs.

The Tesla example illustrates the concept of “market tipping points.” VCPAs could function similarly by stimulating early adoption of low-carbon technologies in HTA sectors, potentially triggering a broader market shift towards sustainable practices.

Raynor emphasizes the urgency of addressing climate change, stating that the timeframes associated with traditional market transitions are insufficient. VCPAs, he argues, offer a mechanism for companies to proactively drive decarbonization efforts in HTA sectors.

Additional Reading on VCPAs

Raynor, Michael. Deloitte. Demand better. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/about-deloitte/us-demand-better-pov.pdf

The Collaboration Gap

Peter Senge, Senior Lecturer of Leadership and Sustainability, facilitated a session called “The Collaboration Gap.” This interactive session engaged participants in collaborative discussions, prompting reflection on the conference’s key themes and emerging questions.

A Model for Sustainable Living

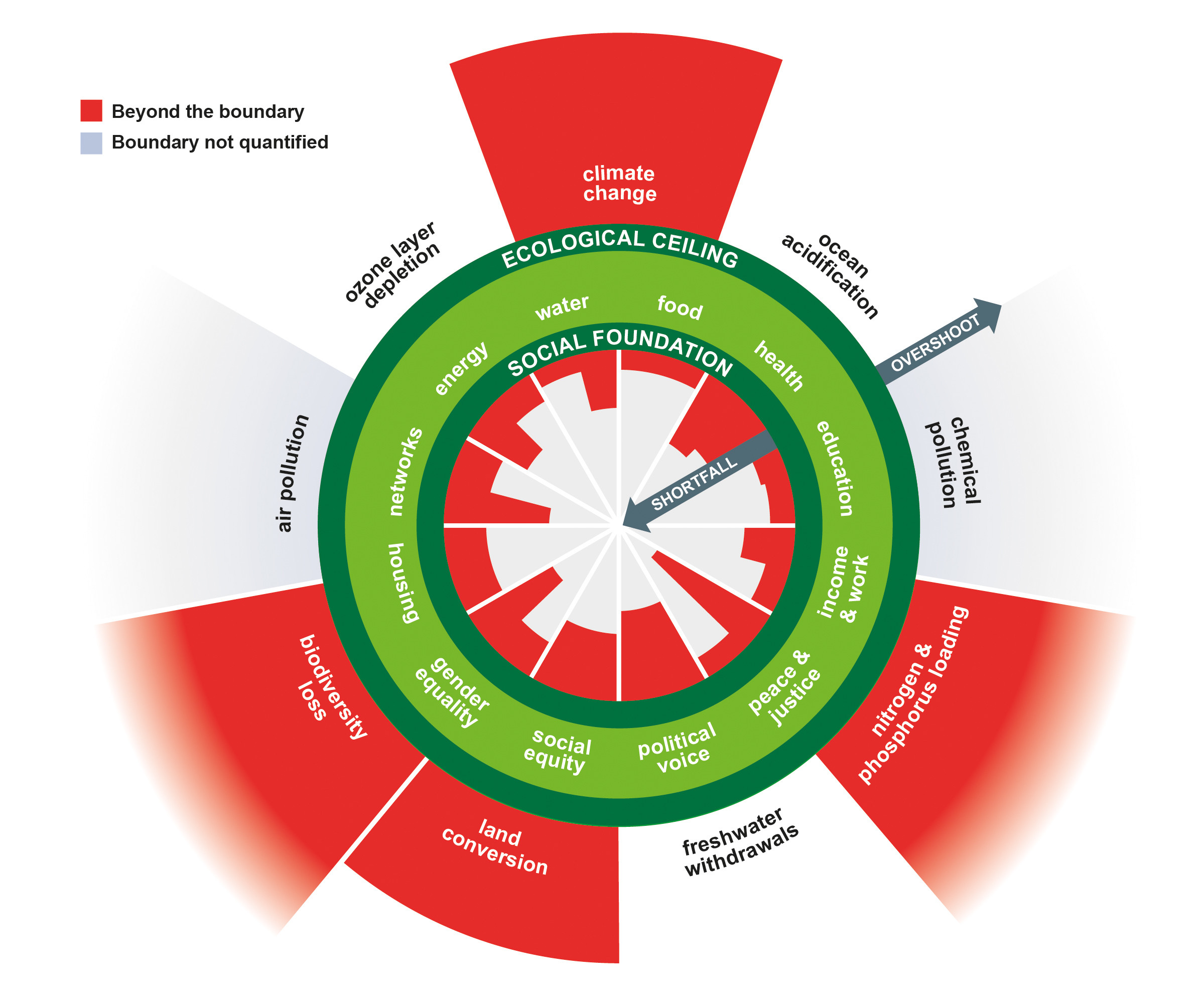

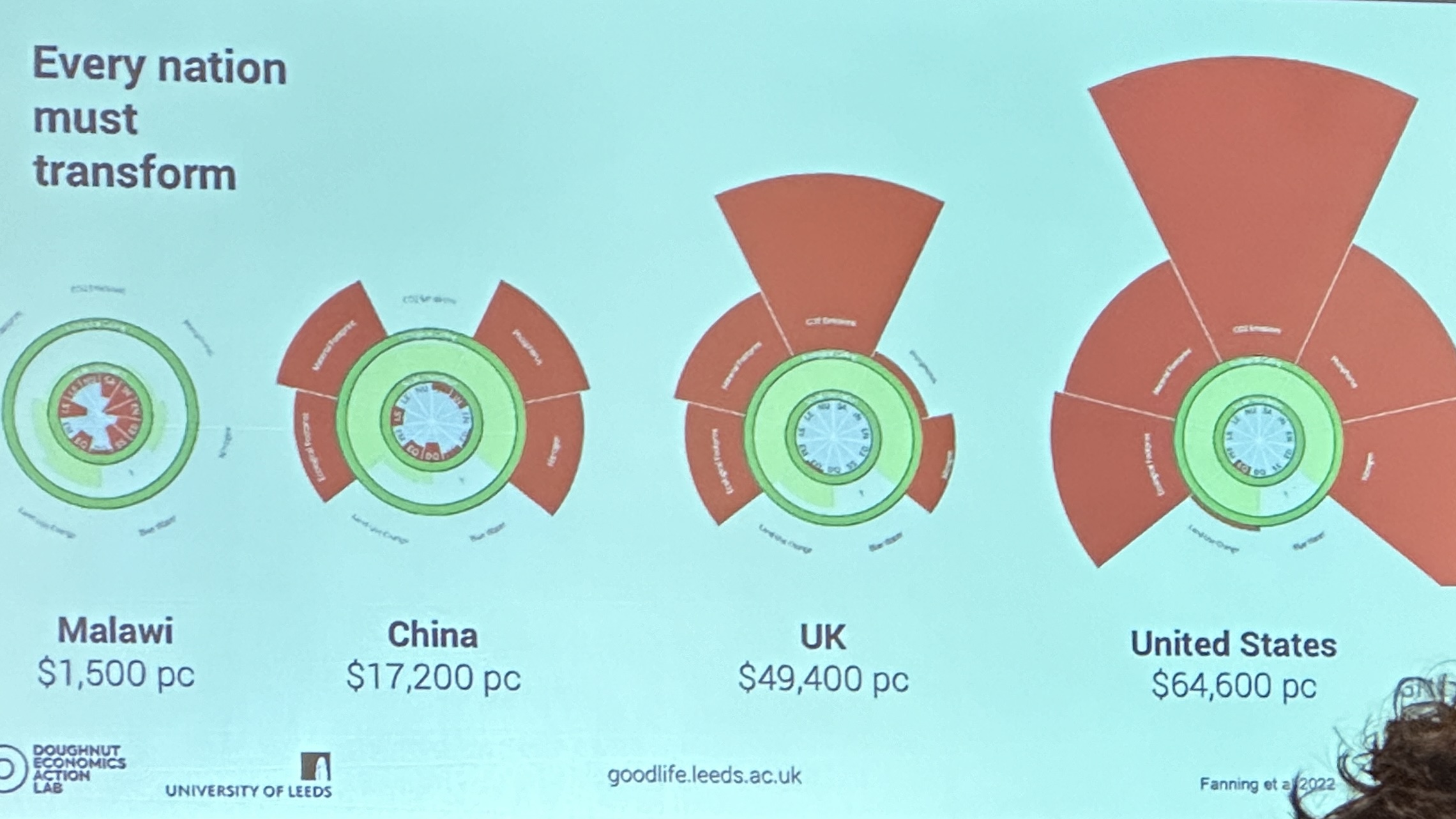

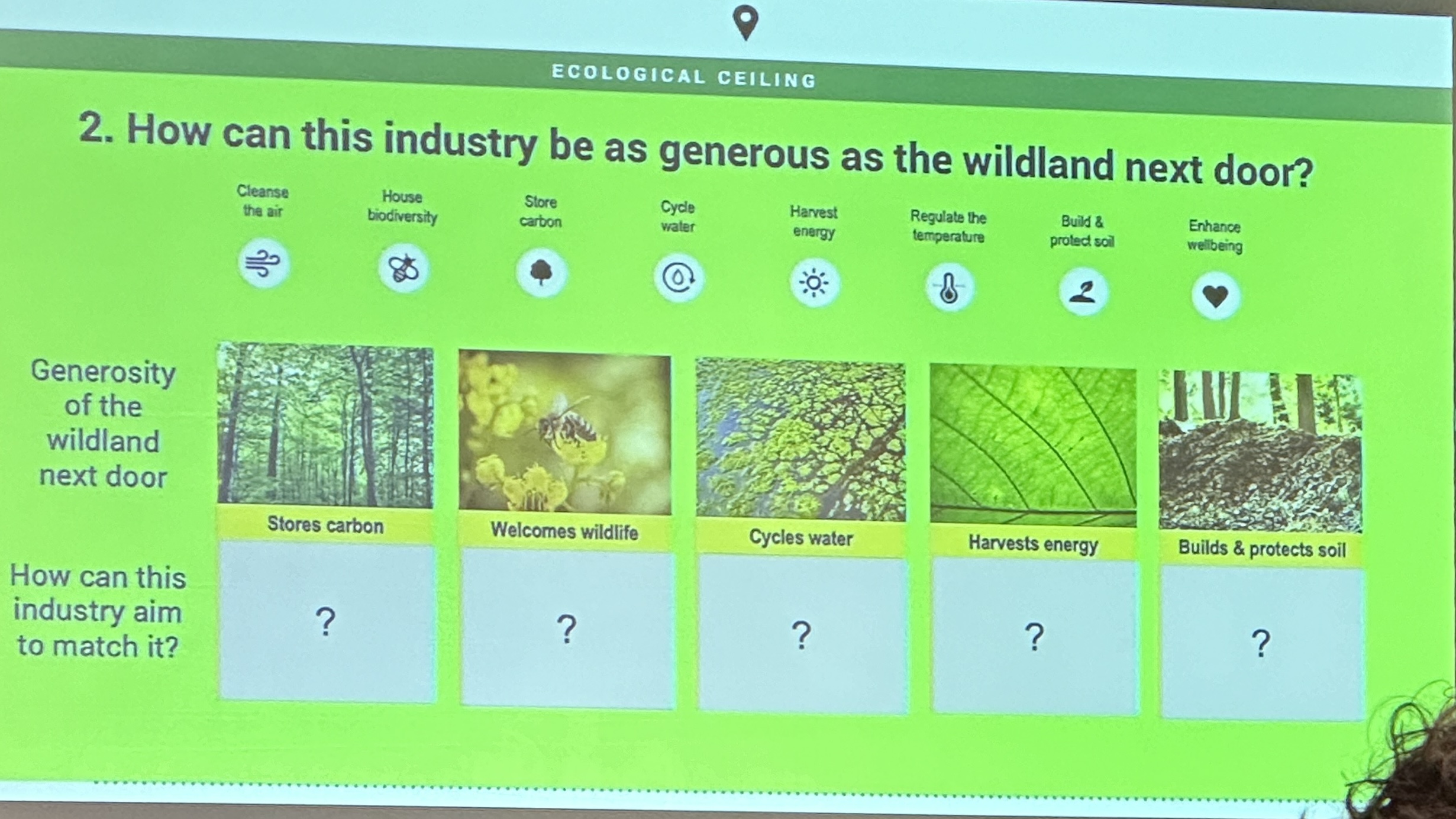

Kate Raworth, known for her “donut economics” model, stressed the urgent need for every nation to undergo a transformative shift towards sustainability. She urged industries to adopt the generosity of nature as a model for their operations, emphasizing the importance of asking a crucial question: “How can this industry be as generous as the wildland next door?”

Raworth highlighted five key characteristics of nature’s generosity that industries should emulate: carbon storage, welcoming wildlife, water cycling, energy harvesting, and soil building and protection. She proposed a framework for analyzing industries based on their ability to match these characteristics. Additionally, Raworth emphasized the importance of purpose, networks, governance, ownership, and finance in driving sustainable transformations across all sectors.

Image: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

Reviving Biodiversity: Costa Rica’s Systemic Shift to Ensure Nature Conservation

Carlos Alvarado Quesada, Former President of Costa Rica, shared insights from his country’s successful model of prioritizing environmental protection alongside economic growth. Under his leadership, Costa Rica banned fossil fuels, committed to carbon neutrality by 2050, expanded protected ocean territories to 30%, and launched the “Costa Rica Green and Blue Agenda 2030” to champion sustainable development and nature conservation.

Quesada highlighted key components of Costa Rica’s legacy that have contributed to its success:

- The abolition of the army in 1948, allowing for a greater focus on education and environmental protection.

- The allocation of 7.6% of the country’s gross domestic product to education.

- The passage of the National Parks Law in 1970, marking a significant commitment to conservation.

- The achievement of a 99.8% clean electricity mix, demonstrating a successful transition to renewable energy sources.

Visioning for a Different Future, Emergence Theory, Historical Example of Rapid Transformation

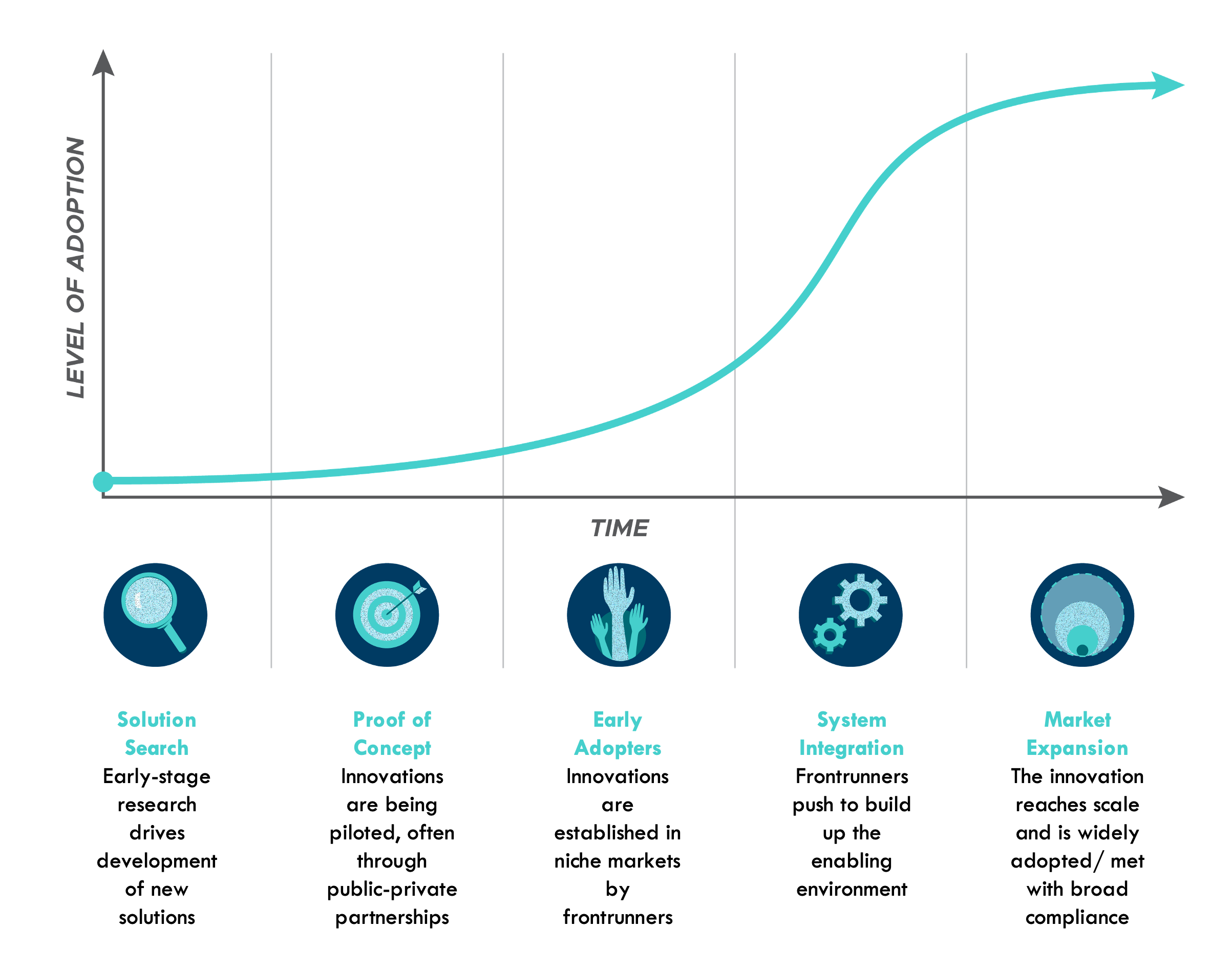

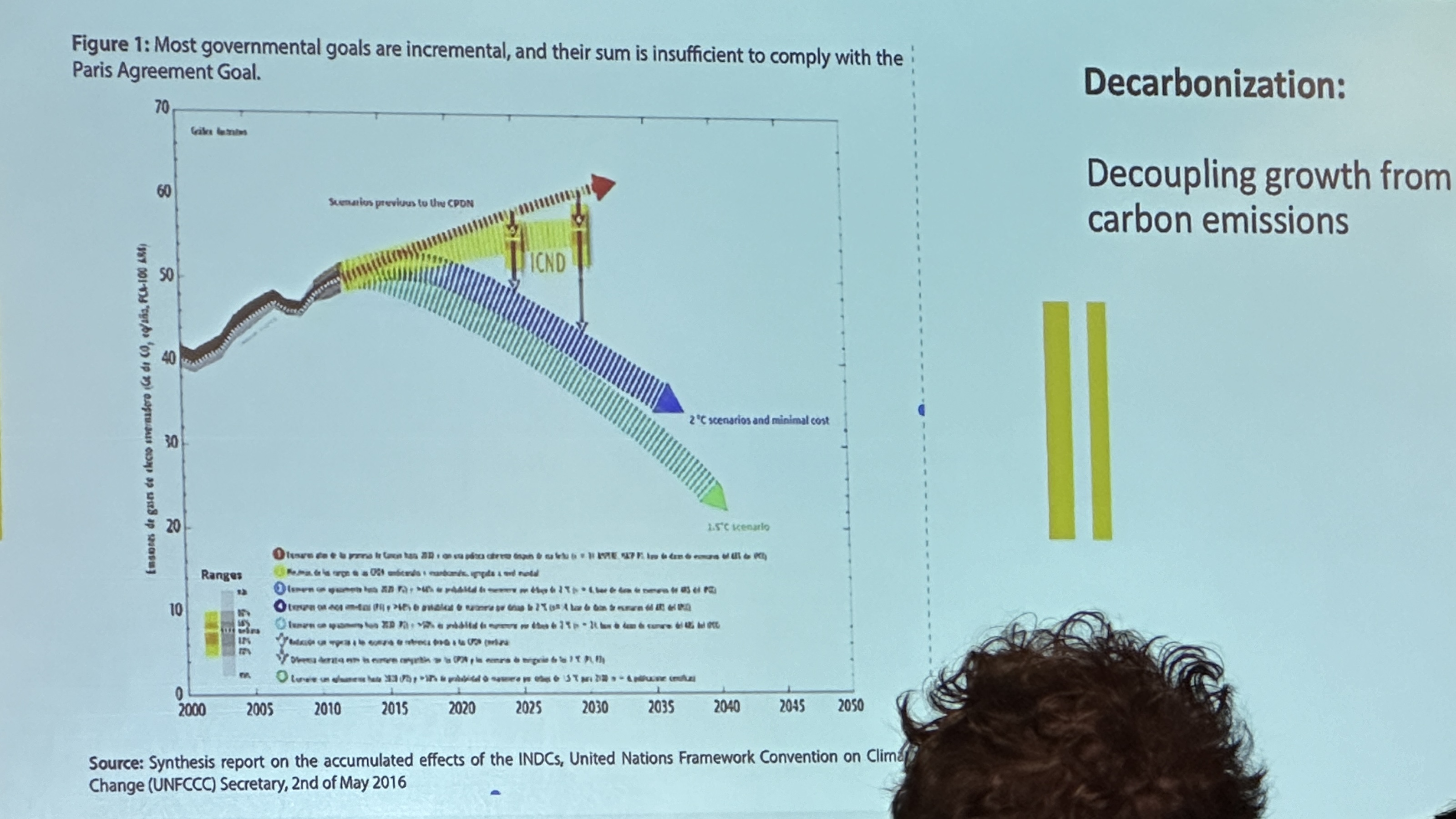

Laurens Speelman, Principal at the Rocky Mountain Institute, focused on the power of “s-curves” in driving rapid transformation, particularly in the context of accelerating low-carbon innovation. Highlighting the urgency of the climate crisis, he framed the energy transition as a “technological revolution with a deadline.”

Speelman argues that traditional, incremental approaches to decarbonization are insufficient to meet the ambitious goals of the Paris Agreement. Instead, a focus on accelerating the adoption of existing green technologies through a deep understanding of S-curve dynamics is essential.

The Power of Exponential Growth

Speelman highlights that analysts consistently underestimate the speed at which green technologies improve and decline in cost. This underestimation stems from a linear view of progress, failing to recognize the exponential growth potential inherent in S-curves. As experience with a technology grows, production processes become more efficient, leading to rapid cost reductions. This cost reduction, coupled with performance improvements, drives increased adoption, further accelerating progress down the S-curve.

Strategic Interventions for Accelerated Transition

Speelman outlines a five-phase framework for understanding and accelerating transitions through strategic interventions tailored to each stage of the S-curve:

- Solution Search: Identify promising innovations with high decarbonization potential, like green hydrogen or sustainable aviation fuels.

- Proof of Concept: Demonstrate the technical feasibility of these innovations through pilot projects and prototypes.

- Early Adopters: Cultivate niche markets for early adoption, supporting cost reductions and demonstrating viability.

- System Integration: Facilitate the integration of the innovation into mainstream markets by developing infrastructure, regulatory frameworks, and workforce skills.

- Market Expansion: Manage the transition, mitigating potential losses, adapting the innovation to new markets, and fostering ongoing innovation.

Speelman emphasizes that different strategies are required for each phase of the S-curve. For instance, during the “Early Adopters” phase, demand-side policies like subsidies or public procurement can be highly effective in creating initial markets. As the innovation matures and enters the “System Integration” phase, the focus shifts to building out infrastructure and establishing industry standards.

Speelman concludes by emphasizing the urgency of the climate crisis and the need for bold, decisive action. By understanding the dynamics of S-curves and deploying targeted strategies, policymakers, businesses, and investors can unlock the transformative potential of existing green technologies and accelerate the transition to a sustainable future.

Speelman, L., & Numata, Y. (2022). A theory of rapid transition: How S-Curves work and what we can do to accelerate them. https://rmi.org/insight/harnessing-the-power-of-s-curves/

Afternoon Track Previews

Track 1: Biodiversity and Agriculture

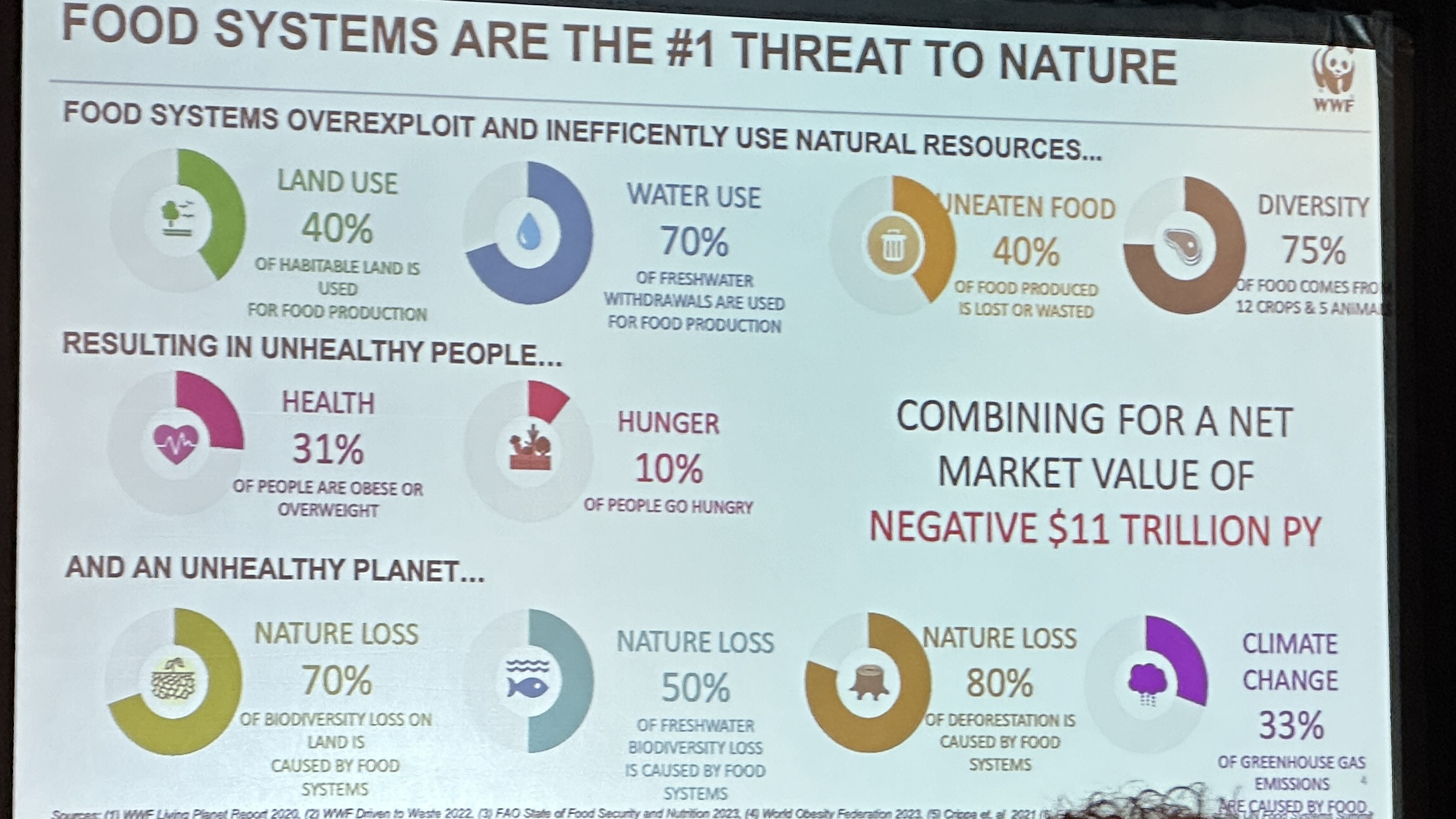

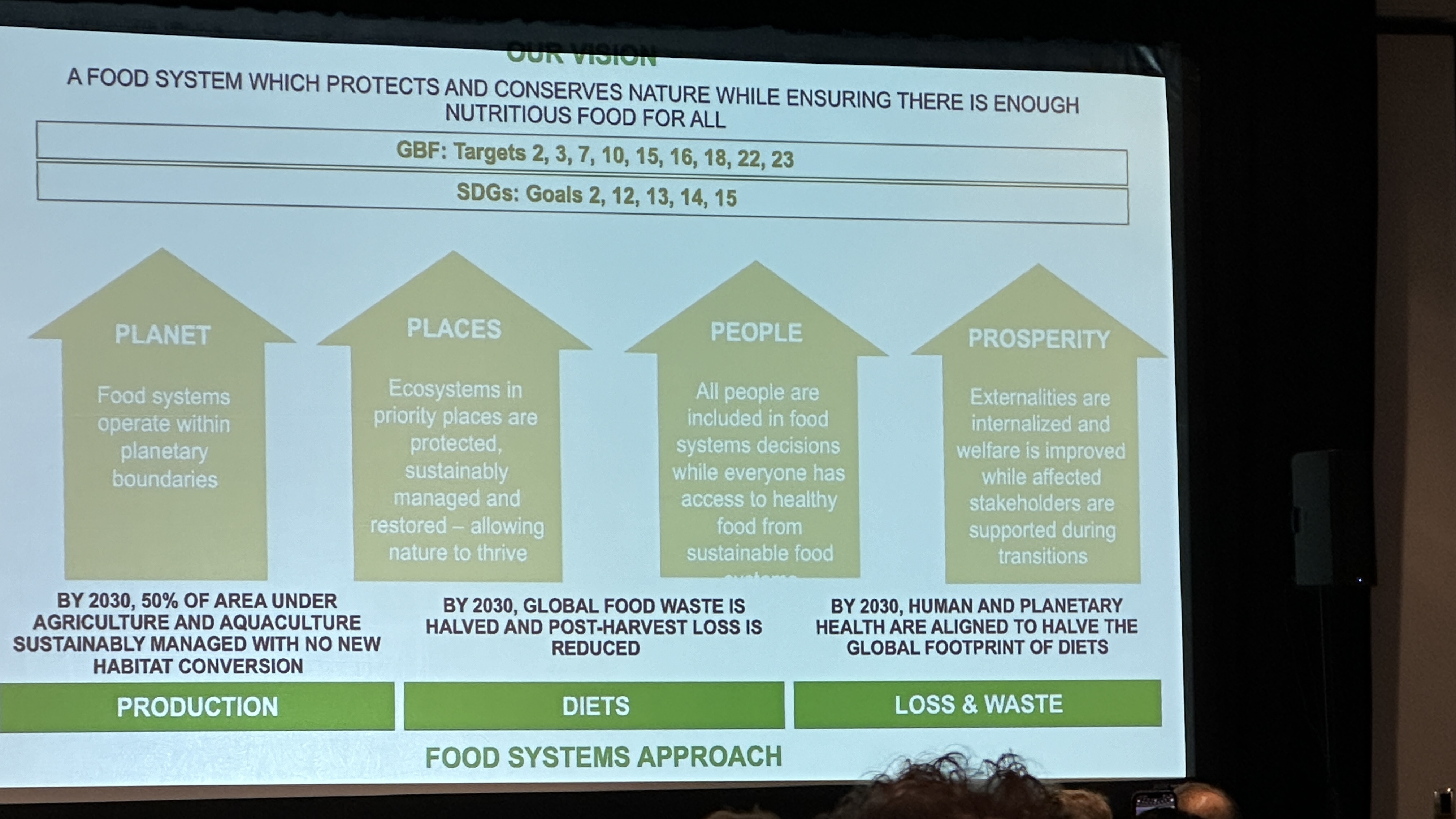

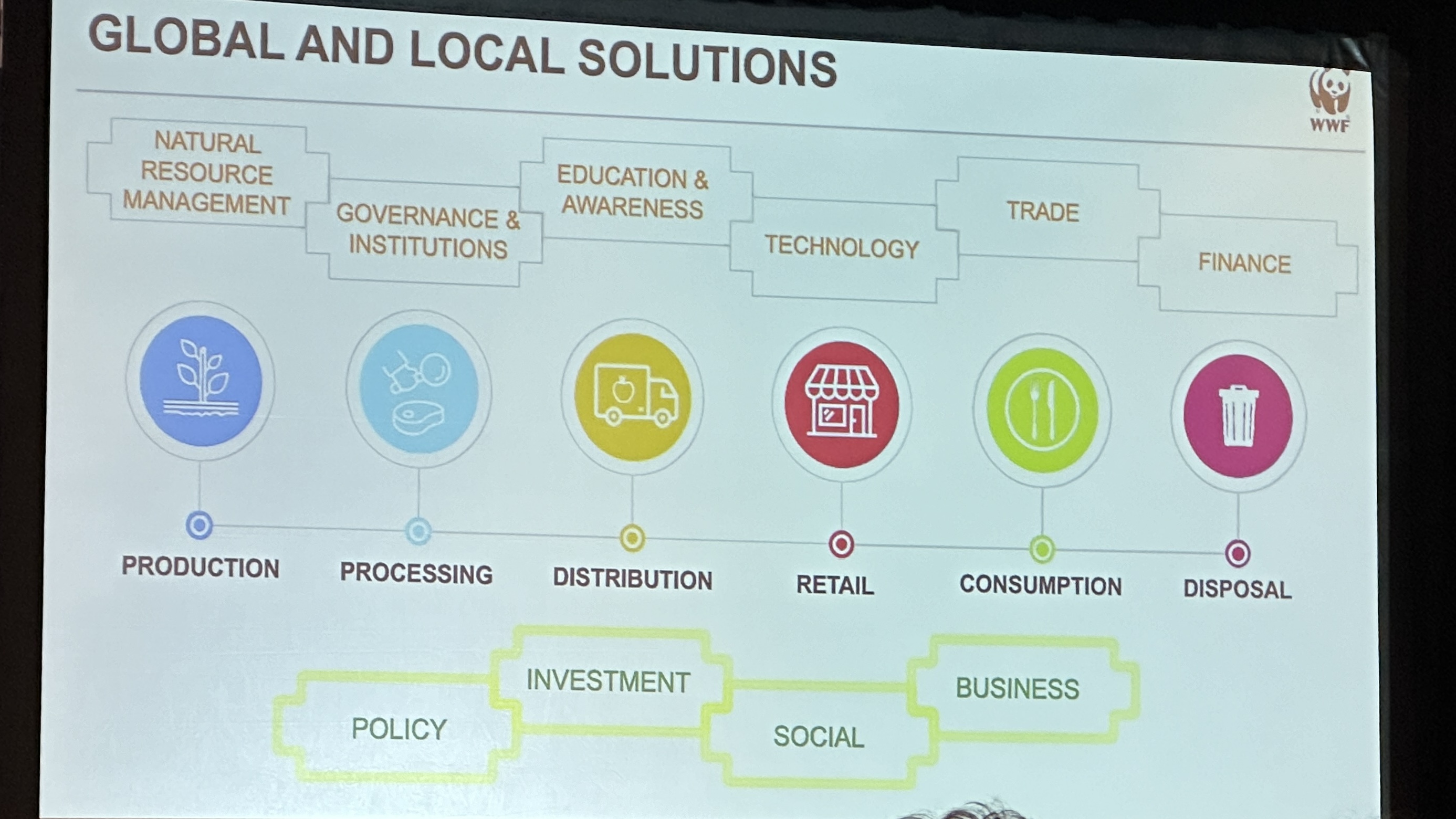

Joao Campari, Global Leader of the Food Practice at WWF International, emphasized the critical role of the food system in achieving global sustainability. He presented a data-driven overview of the interconnected challenges and opportunities within this sector:

Challenges

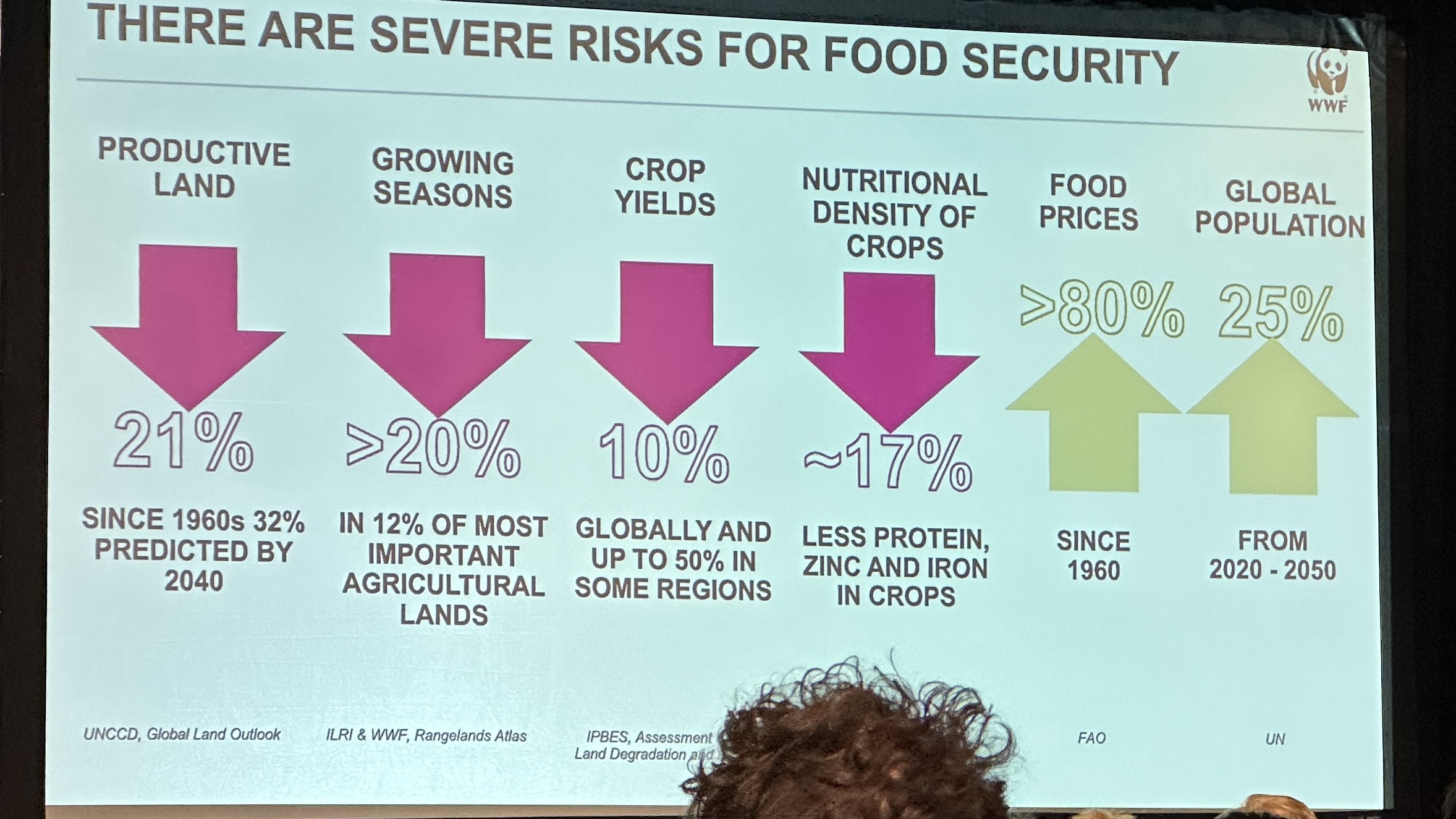

- Land Degradation: A 21% decrease in productive land since the 1960s, with a projected 32% decrease by 2040 (UNCCD, Global Land Outlook). A greater than 20% decrease in growing season length in 12% of key agricultural areas (ILRI & WWF, Rangeland Atlas). A 10% decrease in crop yields globally, reaching up to 50% in some regions (IPBES, Assessment of Land Degradation).

- Nutritional Decline: An approximate 17% decrease in the nutritional density of crops, including protein, zinc, and iron.

- Food Insecurity: 10% of people worldwide, and an alarming 55.2% of people in Brazil, experience food insecurity, highlighting a stark contrast between food production and access. (Rede PENSSAN. (2021). Inquérito Nacional Sobre Insegurança Alimentar No Contexto Da Pandemia Da Covid-19 No Brasil.)

- Health Impacts: 31% of adults are overweight or obese, indicating a need for healthier and more sustainable diets.

- Biodiversity Loss: Food systems are the number one threat to nature, driving 70% of biodiversity loss on land, 50% of freshwater biodiversity loss, and 80% of deforestation.

- Climate Change: Food systems are responsible for 33% of global greenhouse gas emissions, underscoring the urgent need for sustainable practices.

Opportunities

- Sustainable Land Management: Transitioning to regenerative agricultural practices that prioritize soil health, biodiversity conservation, and water conservation.

- Food Loss and Waste Reduction: Addressing the 40% of food that is currently lost or wasted throughout the supply chain.

- Dietary Shifts: Promoting healthier and more sustainable diets that reduce reliance on resource-intensive products.

- Innovation and Technology: Investing in innovative technologies and approaches that can enhance food production efficiency and reduce environmental impact.

- Policy and Investment: Implementing supportive policies and unlocking investment capital to accelerate the transition to sustainable food systems.

Campari outlined six key steps in the food lifecycle that require attention: production, processing, distribution, retail, consumption, and disposal. He emphasized the importance of global and local solutions encompassing policy interventions, investment strategies, social change initiatives, and business involvement across all six stages.

Track 2: Built Environment

Diane Hoskins, Global Co-Chair of Gensler and MIT alumna, focused on the crucial role of the built environment in achieving sustainability goals. She highlighted the significant contribution of embodied carbon emissions during the construction phase, noting that they account for three-quarters of a 20-year-old building’s total emissions.

Hoskins emphasized the importance of addressing the carbon footprint of materials like concrete, the second most used material globally after water. She discussed Gensler’s commitment to developing material standards through their GPS (Gensler Performance System) platform, with version 2.0 specifically addressing concrete, steel, and glass.

She showcased three case studies demonstrating Gensler’s approach to sustainable design:

- SFO Harvey Milk Terminal 1 in San Francisco, CA: Achieving a 79% reduction in total 50-year carbon footprint, over 90% waste diversion, and over 50% reduction in potable water use through innovative design and material choices.

- Nvidia Headquarters in Santa Clara, CA: Utilizing open atriums, abundant daylight, fresh air ventilation, and solar panels to minimize energy consumption and achieve LEED Gold certification.

- 633 Folsom in San Francisco, CA: Demonstrating the benefits of adaptive reuse by structurally reusing an existing building, saving 3 million kg of CO2 emissions, and achieving LEED Gold certification.

Hoskins’ presentation underscored the significant impact that sustainable design choices and material innovations can have on reducing the carbon footprint of the built environment.

Track 3: Transportation

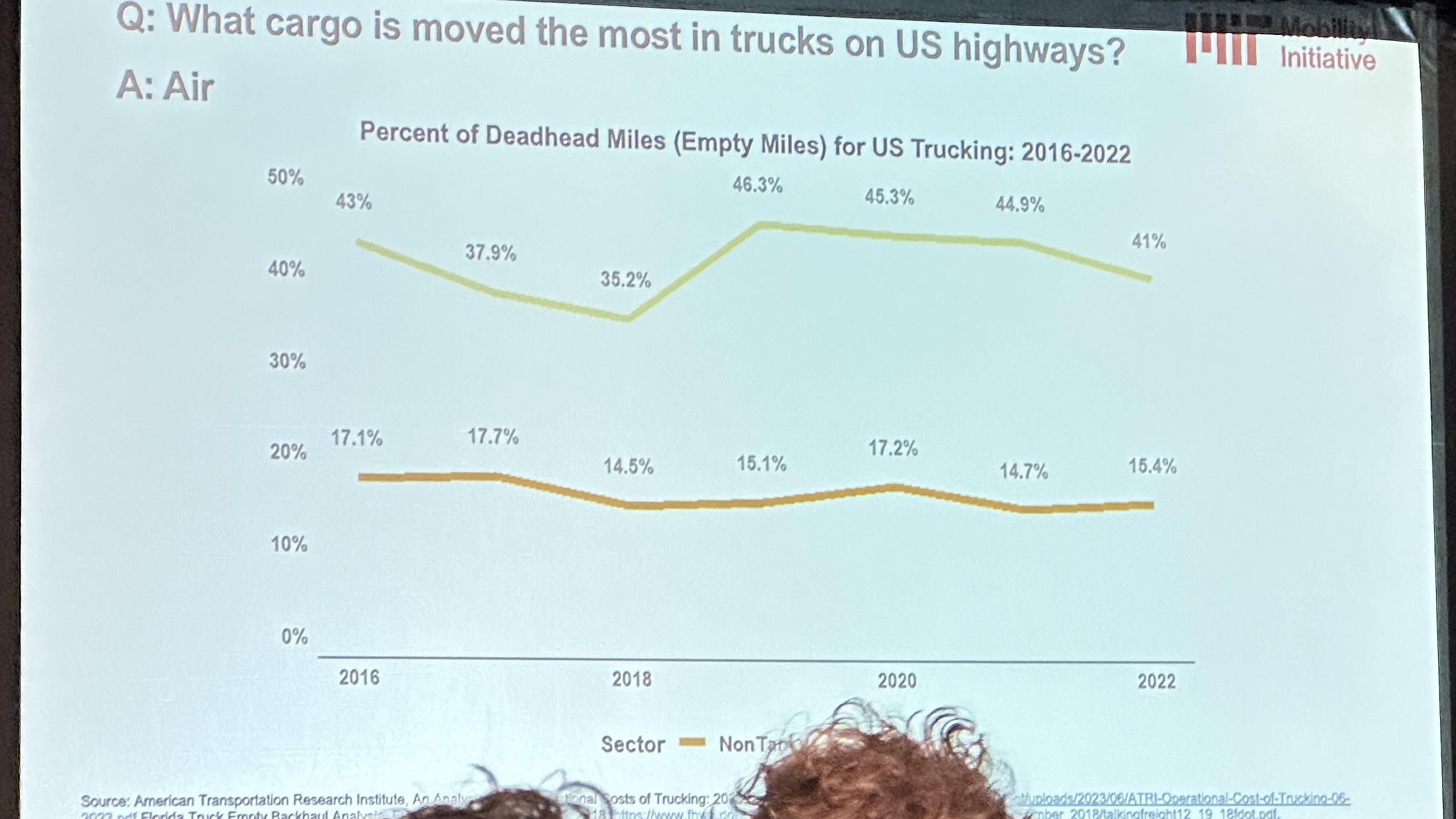

John Moavenzadeh, Executive Director of the MIT Mobility Initiative, addressed the complexities of decarbonizing the transportation sector. He highlighted the issue of “deadhead miles” in the trucking industry, where one out of every six trucks on US highways travels empty.

Moavenzadeh discussed the challenges and opportunities associated with electrifying the trucking industry, including the need for robust charging infrastructure along interstate highways. He also explored the trade-offs between electrifying personal cars and promoting mode shift towards alternative forms of transportation.

He raised important considerations regarding the environmental impacts of battery disposal, particularly groundwater contamination. Moavenzadeh also emphasized the significant role of urban design in reducing transportation needs, advocating for strategies like:

- Establishing micro fulfillment centers for efficient last-mile delivery.

- Implementing smart delivery lockers to minimize delivery trips.

- Promoting cargo micro-mobility solutions for urban freight movement.

- Optimizing curb management strategies to improve traffic flow and reduce congestion.

Moavenzadeh’s presentation emphasized the need for a systemic approach to decarbonizing transportation, encompassing technological advancements, infrastructure development, policy interventions, and behavioral shifts.

What Can One Person Do?

John Sterman, Director of the MIT System Dynamics Group, concluded the morning sessions with a thought-provoking presentation on systems thinking and individual action in the face of climate change.

Sterman used a compelling analogy comparing a slinky and a paper towel roll to illustrate the importance of understanding underlying system structures. He argued that while gravity acts on both objects, their internal structures dictate their resilience and ability to withstand external forces.

Sterman urged the audience to remain resilient and optimistic in the face of political and social challenges associated with climate action. He encouraged attendees to maintain their commitment to change and to resist becoming discouraged by naysayers. Drawing parallels to running the Boston Marathon, Sterman likened the fight against climate change to running uphill with a heavy backpack. He urged the audience to persevere, emphasizing the importance of individual and collective action in driving systemic change.

Afternoon Breakouts: Biodiversity and Agriculture

Key Components of Systems Change

- Involves changing or replacing the rules of the game and/or incentives

- Potentially adjusting who is in power in order to be able to change those rules

- Transforming the relationships and interactions among groups of people

- Requires a collective willingness to take risks and collaborate in innovative ways

The afternoon breakout session on “Biodiversity and Agriculture” featured a panel discussion with experts addressing the complexities of sustainable food systems in Brazil. After the panel spoke, each table spent time collaborating on potential solutions to Brazil’s deforestation crisis.

Panelists included:

- Joao Campari: Highlighted the challenges and opportunities in Brazil’s agricultural sector, emphasizing the role of small family farms and the need for supportive infrastructure and policy.

- Tasso Azevedo: Discussed Brazil’s land use emissions, advocating for increased efficiency in cattle ranching, and addressing land degradation resulting from unsustainable practices.

- Marina Piatto: Shared insights from Imaflora’s work on traceability and monitoring in the Brazilian beef industry, emphasizing the importance of transparency and accountability.

- David Bennell: Highlighted the role of investment in driving sustainable food systems, specifically focusing on mobilizing capital for regenerative practices.

- Purvi Metha: Emphasized the importance of inclusive and equitable solutions in addressing climate change’s impact on agriculture, advocating for investment in adaptation strategies.

The panel session concluded with a call for innovative financial mechanisms, solutions for food waste reduction, and a willingness to disrupt existing unsustainable systems.